“Beings still greater than these have passed away-vast oceans have dried, mountains have been thrown down, the polar star displaced, the cords that bind the planets rent asunder, the whole earth deluged with flood-in such a world what relish can there be in fleeting enjoyments?” (Śrīla Bhaktivinoda Ṭhākura in VNB, p. 18)

The precession of the equinoxes is another astronomical phenomenon that seems to involve a contradiction between the Vedic description of the universe and the picture built up in recent times on the basis of observation. According to Vedic literature, the stars and planets execute a continuous daily rotation around a fixed axis that extends from Mount Meru through the polestar. This motion is generally described in such a way as to indicate that the polar axis of rotation is rigidly fixed. Thus we read that “all the planets and all the hundreds and thousands of stars revolve around the polestar, the planet of Mahārāja Dhruva, in their respective orbits, some higher and some lower. Fastened by the Supreme Personality of Godhead to the machine of material nature according to the results of their fruitive acts, they are driven around the polestar by the wind and will continue to be so until the end of creation” (SB 5.23.2-3).

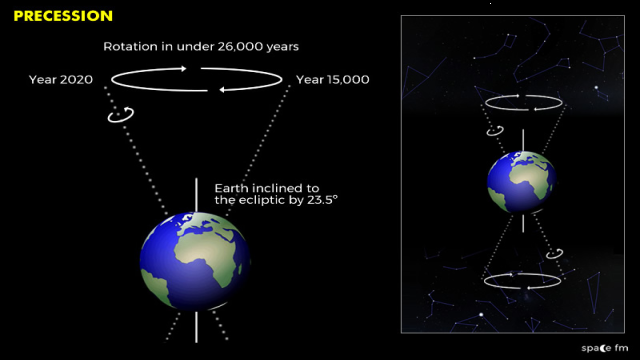

In contrast, it is taught in modern astronomy that the polar axis of rotation is not fixed. It is supposed to rotate slowly about the axis of the ecliptic at a fixed angle of about 23.5 degrees. (The axis of the ecliptic is the line perpendicular to the plane of the ecliptic.) One complete revolution is said to take place in about 25,770 years, and thus the amount of rotation occurring in one year is about 50.29″ of arc. This slow shifting of the polar axis has two important consequences. One is that the position of the equinoxes will rotate slowly around the ecliptic at 50.29″ per year. The equinoxes are the locations of the sun in its orbit at the times of the year when the day and night are of equal length. Since they correspond to the points of intersection between the ecliptic and the celestial equator, they will rotate at the same rate as the polar axis.

The other consequence is that the center of daily rotation of the heavens will move slowly in a large circle centered on the axis of the ecliptic. As time passes, the center of rotation will sometimes lie on a particular star, which will then be known as the polestar. At other times no prominent star will lie at this center. At present the polestar is Polaris, and it is said that in about 12,000 years it will be the star called Vega.

Although this appears to contradict the Vedic view, it turns out, as usual, that things are not as simple as they might seem at first. In the Sūrya-siddhānta there is a rule for calculating something that seems quite similar to the precession of the equinoxes. According to this rule, the position of the sun at the time of the equinox will slowly shift back and forth over a total angle of 54 degrees. The time for one complete back-and-forth movement (covering 54 degrees twice) is given as 7,200 years, and thus the movement occurs at a rate of 54″ of arc per year (SS, pp. 29-30). A rule of this kind is said to describe trepidation of the equinoxes.

This rule seems rather artificial. It assumes that the motion makes an abrupt about face at the endpoints of the 54-degree interval, and thus one suspects that it may be intended simply as a rough approximation. However, it does predict the observed motion of the equinoxes over the period of two thousand years or so for which we have records of observations. And similar rules are given in the jyotiṣa śāstras that smoothly round off the motion at the endpoints of the interval of motion (BJS).

Another consideration here is that in SB 5.21.4-5 the times of the equinoxes and solstices are given relative to the zodiac. These timings are the same as in the Western zodiac. Thus the equinoxes occur in the beginning of the signs Meṣa and Tula, which correspond to the Western Aries and Libra. The Western zodiac moves with the precession of the equinoxes, and thus the equinoxes always occur when the sun enters Aries and Libra. However, the zodiac of the jyotiṣa śāstras has a fixed starting point at the star Zeta Piscium, and thus the position of the equinoxes in this zodiac should shift gradually with the passage of time.

According to modern calculations, the last time the equinoxes occurred at the beginning of Meṣa and Tula was about A.D. 650, and the time before that was some 25,800 years previously. However, according to the trepidation theory of the Sūrya-siddhānta, they would also have occurred at the beginning of Meṣa and Tula at the beginning of Kali-yuga.

In the Siddhānta-śiromaṇi we find the idea that the equinoxes precess through a complete circle. There it is stated that “the motion of the solstitial points spoken of by Muñjala and others is the same as the motion of the equinox: according to these authors its revolutions are 199,669 in a kalpa” (SSB1, p. 157). This comes to about one complete revolution in 21,636 years.

Since Śrīla Bhaktisiddhānta Sarasvatī studied both the Siddhānta-śiromaṇi and the Sūrya-siddhānta, and cited them in his commentary on the Caitanya-caritāmṛta, it would seem that the Vaiṣṇava tradition must include some conception of the precession of the equinoxes. Unfortunately, we have very little information on this topic, and thus further research will be needed to clarify the exact nature of this conception.

As a final point, we should note that according to the modern understanding of the precession of the equinoxes, the present polestar, Polaris, is now about 1 degree from the north celestial pole and will pass within 28′ of it around the year 2100. One thousand years ago, Polaris was about 6.5 degrees away from the pole, and a thousand years before that it was about 12 degrees away. Since 6.5 degrees is about 13 times the width of the full moon, it is hard to see how Polaris could have been regarded as the polestar prior to one thousand years ago.

Due to a lack of suitable bright stars, it would appear that there was no prominent polestar from a few centuries ago back to about 1200 B.C. At about this time the pole passed between Beta Ursae Minorus and Kappa Draconis, and one could have said, roughly speaking, that there were two polestars. To find a prominent, single polestar, however, one would have to go back to about 2600 B.C., when Alpha Draconis was situated at the pole.

We therefore ask, How can this be reconciled with the fact that the Bhāgavatam strongly states the existence of a single polestar? One would think there must have been a prominent polestar when the Bhāgavatam was written. Western scholars maintain that the Bhāgavatam was written about 1,000 years ago, at a time when there had been no notable polestar for thousands of years. Could there be some mistake in the scholarly dating of the Bhāgavatam or in the modern reconstruction of the past history of the polestar, or both? Further research may shed more light on this issue. However, Śrīla Prabhupāda has said, “Whether the Vedic calculations or the modern ones are better may remain a mystery for others, but as far as we are concerned, we accept the Vedic calculations to be correct” (SB 5.22.8p).