The Vedic literature describes the material cosmos as an unlimited ocean situated within a small part of the unlimited spiritual world. Within this ocean there are innumerable universes, or brahmāṇḍas, which can be compared to spherical bubbles of foam grouped in clusters. Each of these universal globes consists of a series of spherical coverings and an inner, inhabited portion.

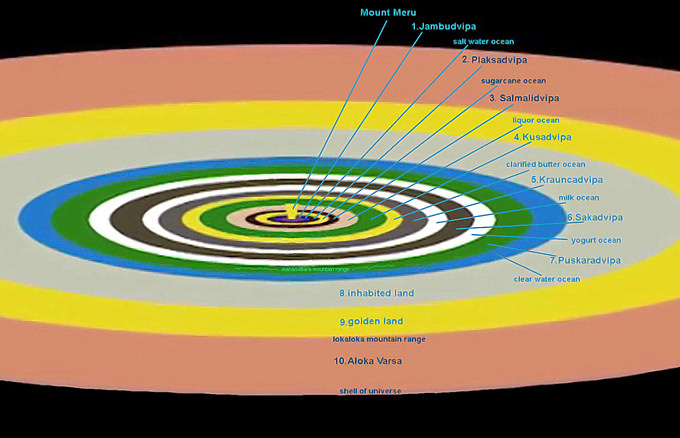

Within the inner region of the brahmāṇḍa, the most striking feature is Bhū-maṇḍala, or the earthly planetary system. Bhū-maṇḍala is described in the Fifth Canto of Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam as a flat disc with a diameter of 500 million yojanas, or 4 billion miles (using 8 miles per yojana). The surface of this disc is marked with a series of ring-shaped oceans and islands surrounding a central island called Jambūdvīpa.

The total surface area of our familiar earth planet is some 197 million square miles, and, according to modern information, the total surface area of the sun is about 2.4 million million square miles. In contrast, the total area of Bhū-maṇḍala comes to about 12.6 billion billion square miles. In SB 2.5.40p Śrīla Prabhupāda refers to this as the area of the universe, and it seems that Bhū-maṇḍala is indeed one of the most significant and frequently mentioned features in the Vedic account of the universe. Its size is on the scale of the solar system as a whole, as conceived in modern Western astronomy.

The Fifth Canto gives specific figures for the size, shape, and position of many of the geographic structures of Bhū-maṇḍala. The most striking characteristic of these structures is that although their description employs names for familiar features of earthly geography, such as mountains, oceans, and islands, they are all on the same cosmic scale as Bhū-maṇḍala itself. Thus the smallest mountains on Bhū-maṇḍala mentioned in the Bhāgavatam are 2,000 yojanas, or 16,000 miles, high. Many mountains are 80,000 miles or even 672,000 miles high. In contrast, the diameter of the earth is about 8,000 miles, and Mount Everest, the highest known mountain, extends about 5.5 miles above sea level. References to such immense sizes are not limited to the Fifth Canto.

For example, SB 4.6.32 gives a description of Lord Śiva meditating underneath a banyan tree 800 miles in height and 600 miles in breadth. In SB 8.2.1 we read that Trikuta Mountain, where the elephant Gajendra achieved liberation, is 80,000 miles in length and breadth. This mountain is situated in the ocean of milk, one of the geographical features of Bhū-maṇḍala. In SB 8.7.9 it is pointed out that when Kūrma, the tortoise incarnation of Lord Viṣṇu, was supporting Mandara Mountain during the churning of the milk ocean, His back extended for 800,000 miles (lakṣa-yojana), “like a large island.” Finally, the Matsya avatāra, Lord Viṣṇu’s fish incarnation, expanded from an initial small size to a final length of 8 million miles (SB 8.24.44).

Modern scholars tend to reject dimensions such as these as ludicrous exaggerations made by poets who were completely devoid of scientific knowledge. However, even common men in primitive societies can tell that the earthly mountains of our experience have heights of thousands of feet rather than thousands of miles. The highly rational philosophical discussions in the Bhāgavatam indicate that it was not written by some kind of mad fanatic who was devoid of common sense. We suggest, therefore, that the descriptions in the Bhāgavatam of gigantic sizes refer to an actually existing world that is built on the scale of the solar system and that contains features built on a similar scale.

We will assume that this is the case, and later on we will consider what the relation might be between this world and the earth of our experience. For the present we will give a brief overview of the most significant features of Bhū-maṇḍala. We will do this with the aid of a series of computer-generated illustrations that portray the features of Bhū-maṇḍala as they would appear to an observer approaching Bhū-maṇḍala from a great distance.

In the first view (Fig. 3) we are looking down on the center of Bhū-maṇḍala at an angle of 45 degrees from a distance of some 600 million miles. We can discern five ring-shaped structures surrounding a central region that is too far away to see clearly. Going from the outside in, these are respectively the dvīpas, or islands, named Puṣkaradvīpa, Śākadvīpa, Krauñcadvīpa, Kuśadvīpa, and Śālmalīdvīpa. Puṣkaradvīpa has inner and outer radii of 100.4 million and 151.6 million miles, and each successive ring, going inward, is half as wide as the one preceding it. To give an idea of the scale, the distance from the earth to the sun is currently accepted to be 93 million miles.

The intervals between the dvīpas are occupied by oceans, each of which has the same width as the dvīpa that it surrounds. The oceans surrounding the five dvīpas we have mentioned are said to be composed respectively of clear water, yogurt, milk, ghee, and liquor. Of course, these substances are celestial counterparts of the corresponding ordinary substances of our day-to-day experience. In Figure 4 we have moved in to a distance of about 150 million miles from the center of Bhū-maṇḍala. Now Krauñcadvīpa, Kuśadvīpa, and Śālmalīdvīpa have expanded in apparent size, and the ring of Plakṣadvīpa has become visible within Śālmalīdvīpa. We can also begin to discern the central island of Jambūdvīpa within Plakṣadvīpa.

In Figure 5 we have moved in to a distance of 15 million miles, and in Figure 6, at a distance of some 3 million miles, we can obtain a detailed view of Jambūdvīpa.

Jambūdvīpa is described as a disc-shaped island 100,000 yojanas, or 800,000 miles, in diameter. (For comparison, the currently accepted diameter of the sun is 865,110 miles.) The most striking feature of Jambūdvīpa is a central structure called Mount Meru, which is 84,000 yojanas high. This structure is generally referred to as a mountain, although it clearly has a unique form quite different from that of a typical mountain. The upper surface of Mount Meru is said to be occupied by Brahmapurī, the city of Lord Brahmā, and by cities belonging to eight other demigods.

Jambūdvīpa is divided into nine regions, or varṣas, by a series of mountain ranges. In Figure 7 we see a more detailed view of the central region of Ilāvṛta-varṣa, which contains Mount Meru and is square in shape. To get some idea of the scale of this figure, we should note that the low mountain chain stretching from A to B in the figure is called Gandhamādana and reaches 16,000 miles in height. This is twice the diameter of the earth.

Of the nine varṣas of Jambūdvīpa, eight are described as places of heavenly enjoyment. These are intended for persons who have returned to earth after using up their allotted time on the heavenly planets but who have some remaining pious credits entitling them to enjoy great material opulence. The inhabitants of these varṣas are described as living for 10,000 years by earthly calculations, as having the bodily strength of 10,000 elephants, and as having a standard of pleasure like that of the human beings of Tretā-yuga (SB 5.17.12). These regions are also said to contain beautiful gardens that are visited by important leaders among the demigods. The Bhāgavatam refers to these eight varṣas as bhauma-svarga, or the heavenly places on earth (SB 5.17.11), while Śrīla Prabhupāda describes them as “the lower heavenly planets” and contrasts their inhabitants to those of “this earth” (SB 5.17.13p).

The remaining varṣa of Jambūdvīpa is called Bhārata-varṣa. It is described as the field of fruitive activities, in which human beings struggle with adverse conditions and elevate or degrade themselves by their actions. Bhārata-varṣa is the southernmost region of Jambūdvīpa, and it is illustrated in Figures 8 and 9, in which we view Jambūdvīpa from the southeast at a lower elevation. In shape, Bhārata-varṣa is a semicircular piece of land bounded on the south by the salt-water ocean and on the north by the Himalayan Mountains. Bhārata-varṣa is the only part of Bhū-maṇḍala at all reminiscent of the earth, and it is frequently identified with either the earth or with India in Śrīla Prabhupāda’s books.

Yet the Himalayas bounding Bhārata-varṣa are described in the Fifth Canto as being 80,000 miles high, and Bhārata-varṣa itself runs some 72,000 miles (9,000 yojanas) from north to south. This naturally leads us to ask, What is the relationship between the earth of our experience and Jambūdvīpa and Bhārata-varṣa, as described in the Śrīmad-Bhāgavatam?